When the COVID-19 pandemic halted the world in March 2020, records managers had to keep going. On May 4, 2020, a group of leading memory organizations around the world—including U.S.-based records management association ARMA International—called for the perseverance of good records management by governments, schools, research institutions, and businesses in a statement titled “COVID-19: The Duty to Document Does Not Cease in a Crisis, It Becomes More Essential.”Kyna Herzinger, records manager for the Presbyterian Historical Society of Louisville, Kentucky, and before that, archivist for university records and records manager at the University of Louisville, said in an email interview, “I would characterize the biggest challenge [of this duty] as a loss of control over how and where records are being stored—and by extension the security and accessibility of those records. After the initial lockdown, as we all started getting the sense that we were going to be in it for a while, I was worried that folks might take physical records home with them. Little did I know that I should have been worrying about digital storage!”

ADAPTING TO REMOTE WORKERS

Rebecca Hanna, government information analyst at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission (TSLAC), in “Creating Records At Home, Part III: Various Devices” from June 1, 2021, suggested that records managers add rules for management of work records created in the home to remote work policies. An important rule was persistence with records management practices while at home. Another imperative was that employees should always work inside their employer’s network and store digital records in official storage locations as designated by records managers and avoid records storage on personal devices. Hanna’s article offered graphics to help get the conversation started, including:

Source: Texas State Library and Archives Commission; used with permission

Source: Texas State Library and Archives Commission; used with permission

If employees must use personal storage, they should migrate digital records to official storage at the first opportunity and delete all copies on local storage, wrote Hanna and TSLAC government information analyst Erica Siegrist in “TSLAC Guidance for Records Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic” from Aug. 9, 2021. Records managers should give guidance for home printing on “how, when, or even if employees may print government records at home.”

Herzinger provided one-on-one guidance to her colleagues about preferred locations for digital storage when working from home, noting, “Folks who used remote desktops were sometimes unclear about the environment they were working in. I got the sense that folks turned to storing records in what they felt most comfortable navigating: Google Drive, Dropbox, a local desktop, or for some even just their email client. I still see these trends of relying not on the best storage, but the most convenient storage.”

At Herzinger’s current organization, a recent technology assessment recommended digital storage standardization in a cloud-based solution. While this assessment was unrelated to the pandemic, “I do suspect that the pandemic reinforced and heightened its importance. The simple act of creating a standardized approach for where folks can save the records they create in our fluid work environments is a big boon,” she said. “As the records manager, I do have a voice in the process. That said, the ‘umph’ of getting this done is happening at a higher level, the importance of which cannot be understated.”

MANAGING VIRTUAL COLLABORATION

During the pandemic, people were still able to meet, talk, and sometimes see colleagues’ faces (and children and kitchens). Videoconferencing went mainstream, and out-of-the-ordinary records such as meeting recordings and chat logs needed managing.

Most virtual meetings replaced face-to-face discussions that, pre-pandemic, didn’t result in records, TSLAC government information analyst Erica Rice wrote in “Creating Records at Home, Part II: Zoom” from Jan. 12, 2021. So, unless required by laws or pre-pandemic procedures, most virtual meetings didn’t need recording. Records managers could write a virtual meetings policy with criteria for when to record or when minutes were enough, the official storage location for digital video files, and whether to use the videoconferencing platform’s own cloud storage. Noting that videoconferences generate chat logs, Rice recommended limiting chats to small talk. Chats that go beyond small talk and into official business are records. In these cases, the policy says who is responsible for preservation of the chats.

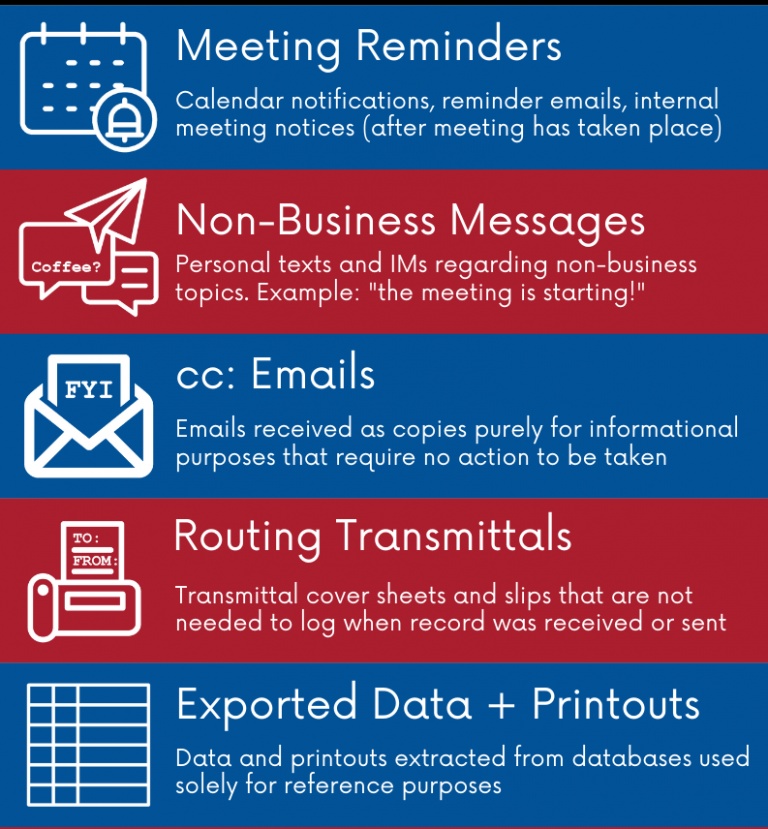

Workers also learned to share documents, assign tasks, and instant message on collaboration platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Microsoft SharePoint. In “Creating Records at Home, Part I: Microsoft Teams” from July 14, 2020, TSLAC’s Rice wrote about the easy option for records managers: Just ask people to share only transitory information when on the platform. Transitory information does not document official business and may be deleted after use. It includes:

Source: Texas State Library and Archives Commission; used with permission

Source: Texas State Library and Archives Commission; used with permission

As the pandemic wore on and collaboration platforms caught on, however, they hosted real work and real records. In “Records Management in Teams,” the Indiana Archives and Records Administration (IARA) combined records management with the Indiana Office of Technology’s Teams lifecycles and devised Teams Types, “a no cost, low tech, medium maintenance approach to managing records in Teams” featuring the following:

- Administrative Teams—for distribution of routine information; no original records stored in Teams; messaging turned off

- Collaborative Teams—for projects lasting 6 months to 2 years; records are working drafts or copies of originals stored outside of Teams; messaging turned on

- Executive Teams—used by managers for policy, legal, or internal actions; records are working drafts or copies; messaging turned off

All Teams were to designate a member for records cleanup by the rules of that Teams Type.

According to TSLAC’s Rice, this was an opportunity for records managers to collaborate with IT colleagues on enterprise-level configuration of these platforms for records management. “With complex, enterprise-wide software like Teams, usually no one outside of the IT department will have the ability to edit permissions, to apply retention rules, or to just fiddle with the general software settings. Let IT know what your retention requirements are: your wildest dreams AND your bottom-line, minimum ‘must-haves,’ ” wrote Rice.

ARCHIVING A GLOBAL PANDEMIC

The May 4, 2020, international “Duty to Document” statement also called for the collection and preservation of pandemic-related records “not only to prevent and/or anticipate similar events but to understand the effect this event will have on current and future generations.”

Records managers and archivists must change and “broaden their collecting scope,” wrote Rebecca McGee-Lankford, assistant state records administrator for the State Archives of North Carolina, in “COVID-19 and Local Government Agency Records” from May 4, 2020. They must appraise records that, pre-pandemic, were not archival, but now may have historical value, write new retention schedules for new types of pandemic-related records, and archive new social media accounts and websites that disseminate essential information. The “Duty to Document” statement asked archivists also to take custody of algorithms and the “rough or raw data” of the pandemic.

In “Documenting COVID-19” from April 1, 2020, the Alabama Department of Archives & History suggested these records for archival appraisal:

- Informational materials (graphics, posters, guidance, newsletters, etc.)

- Press releases

- COVID-19 committee/task force meeting minutes

- Photographs

- Video recordings of announcements, press conferences, etc.

- Administrative files of agency leaders

- Planning and policy documentation, especially documentation of modifications to services, policies, or future plans

- Legal opinions and guidance

- Important communications and correspondence with staff or external stakeholders

- Any other historically significant information

Pandemic-related records may inundate archivists and records managers. Herzinger said, “[T]he number of paper records I received in 2021 exploded when folks started returning to the office. That summer and through the fall, I received more than double the normal amount of mostly permanent and some non-permanent records. As both the records manager and the archivist, I was incredibly busy accessioning and processing archives materials.”

BLURRING BOUNDARIES

Because emergency preparedness is part of records management, records managers were ready for the pandemic. They reminded colleagues to stick with records management programs while working from home. While working from home themselves, they created records management guidance for new situations and technologies. They predicted what records needed archival preservation for future historians.

Herzinger concluded:

Right now, I’m hyper-focused on where folks are storing their records—a clever colleague dubbed me the ‘broken record, records manager’—and trying to encourage good choices. But I’m also trying to acknowledge the messiness of the boundaries between our work lives and personal lives. If a person uses the same device to do work stuff and personal stuff, it can leave a digital trail. And if as an organization we want to promote good data management, staff need to be cognizant of the times that a water bill is being automatically saved to a downloads folder or when that Grateful Dead album is saved to a ‘My Music’ folder. I’m also learning that good records management is enhanced by a basic understanding of how our systems actually work. In short, the pandemic changed my records management stump speech.

10 ACTION STEPS FOR RECORDS MANAGERS

The following are 10 steps records managers can take as the world slowly emerges from the pandemic:

- Write records management policies for home-based staff.

- Make sure everyone has access to official storage for digital records.

- Write a records management policy for virtual meetings.

- Work with IT colleagues on configuration of collaboration platforms.

- Write and promote policies for records management on collaboration platforms.

- Adjust existing records retention schedules for previously routine records that now have archival value.

- Add new pandemic-related records to retention schedules.

- Plan for preservation of websites, social media, algorithms, and data.

- Track all pandemic-related records and accession if they have historical value.

- Update records management training with lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.